Gender amongst NCAA DI and DII Women’s Soccer Coaches

Table of Contents

Write a research proposal on the Topic: Gender amongst NCAA DI and DII Women’s Soccer Coaches. The proposal research proposal should follow the following instructions:

- Cover Page

- Title of Paper (H1)

- Full Name

- Master’s Program

- Institution

- Date (Month Year)

- Introduction

- What is the topic studied?

- What is the theoretical problem presented?

- What is your hypothesis?

- What is the need for the study?

- 1-2 pages

III. Literature Review

- AT LEAST 10 sources

- 5-7 pages in length

- Current literature which supports/opposes your hypothesis empirically and theoretically

- Exhaustive review

- Methods

- 1 page

- Explain the approach taken to collecting data presented in the study.

- Results

- Present data retrieved in a study in graphs, charts, Etc.

- Captions and labels for each graph

- Graphs presented in a uniform manner

- Discussion

- Summarize study theoretical approach

- Summarize results

- Discuss the correlation between hypotheses and results

- Present implications to the field

- 1-2 pages

VII. Reference Page

- APA Formatting

VIII. APA Formatting

- Headings

- Page Numbers

- Margin and line spacing

- In-text citations

- Reference page

Overall Professionalism: No errors in punctuation, capitalization, spelling.

Here is a research proposal example on Gender amongst NCAA DI and DII Women’s Soccer Coaches

PART I: Introduction

The gender dynamic has been a very contentious issue for many decades. This is especially the case because the contemporary world perceives sports as a male-dominated sector when it comes to sportsmen, sportswomen, and their coaches or leaders. Even after including more females in the sports dimension, a sense of gender balance has still not been achieved. Gender inequity is still prevalent, especially when it comes to the representation of female coaches and gender stereotypes. The issue of women’s underrepresentation in leadership positions has become one of the significant challenges facing women in all aspects, including business, politics, and even soccer (Burton, 2015).

This underrepresentation is very lucid in the sports sector, most especially in collegiate sports where male domination exists. This was the case until the authorization of Title IX was enacted in 1972. This legislation led to a significant increase in the number of female athletes (Kahn, 2007). However, this situation did not reflect on the part of DI and DII female coaches. NCAA female coaches had been faced with a wide array of issues before the enaction of Title IX. However, the challenges increased after the enaction, which translated into a tremendous decrease in the number of DI and DII female coaches between 1972 and 2014. While the number of male coaches significantly increased (Acosta & Carpenter, 2014). These figures illustrate the pre-existing gender gap in coaching positions in the NCAA DI and DII intercollegiate athletics.

Putting these numbers into a deeper perspective, the number of female head coaches has only witnessed a slight increase from 29.4% to 31.8% between 1977 and 2014 (Acosta & Carpenter, 2014), while the male coaches almost doubled these statistics. These statistics indicate that numerous barriers are facing the inclusion and participation of female coaches in the NCAA DI and DII college sports, with the main issue being gender. Some researchers have come out to argue that the underrepresentation of female coaches results from poor on-field performance. However, this claim is purely unjustifiable and lacks no ground. Empirical studies conducted by Gomez-Gonzalez et al. (2018) postulate that a team’s on-field performance has no relation to the gender of the team’s coach.

The purpose of this research paper is to carry out a comprehensive and exhaustive empirical evaluation regarding the relationship between the representation of NCAA DI and DII female coaches and gender stereotypes and role incongruities.

This research paper will also analyze the following research questions;

- Does team performance have any effect on the gender of the coach hired?

- How does the gender of the coach affect the probability of coach dismissal after a team performs poorly?

Stereotypes and Role Incongruity

Some of the most significant challenges facing women in NCAA DI and DII soccer coaches include role incongruity and gender stereotypes. Often, people associate most NCAA coaching positions with men (Schein, 1973, 1975). Gender stereotypes have furthered this belief by offering justifications such as perceiving men as bolder, more aggressive, assertive, and agentic. At the same time, women are more relationship-oriented, kind, nurturing, and communal (Haines et al., 2016). Such stereotypes make it much harder for women coaches trying to permeate the field of NCAA DI and DII soccer. Simply put, if there is an alleged incongruity between an individual’s gender role and their leadership role, the individual is less likely to hold any leadership position (Eagly & Karau, 2012). These incongruities result in innumerable prejudices and biases against females.

Studies by Aicher & Sagas (2010) reveal that qualities ascribed to efficient coaches in NCAA DI and DII soccer conform are more masculine than feminine. These studies also decipher those female coaches are more preferred for “feminine” sports such as figure skating or synchronized swimming than “masculine” sports such as soccer. The discrimination and bias faced by female soccer coaches affect their representation and lower remuneration than their male counterparts.

Glass Cliff Postulation

This phenomenon perceives that women in collegiate soccer are most likely to be put in leadership positions such as coaching if precarious situations occur, for example, after consistent team losses (Ryan & Haslam, 2007). May would think that this is done because women are believed to have better chances of leading a change in the team. Unfortunately, studies reveal that this is mainly done to attribute the team’s poor performance to the stereotypical behaviors associated with women (Ryan, 2016).

Additionally, research studies done by Ryan & Haslam (2007) illustrate that soccer teams in collegiate sports that have had a long history of good performance tended to employ more men as coaches, while those with a history of poor performance hired more female coaches. Similar studies by Mulcahy & Linehan (2014) also indicate that women are most likely to be appointed to top positions in an institution or organization when the institutions have been performing poorly. The glass cliff postulation clarifies that gender is one of the variables that affect female coaches in NCAA DI and DII soccer.

PART II: Methodology

Data Collection

Data was gathered from 64 women’s collegiate soccer teams from 11 data seasons between 2007 and 2017 in five conferences. The conferences include South-eastern Conference (SEC), Pac 12, Big 12, Big Ten, and Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). Kansas State was omitted because it did not fit the criteria of having at least 11 data seasons since it became part of women’s college soccer in 2016. the schools used in this study also had substantial budgetary allocations to their women’s soccer teams. 32 schools of 36 schools also produced national champions in their respective conferences (NCAA, 2018). Additionally, the schools were requested to provide us with information regarding their team performance, win and loss records, and the history of their soccer teams’ coaches.

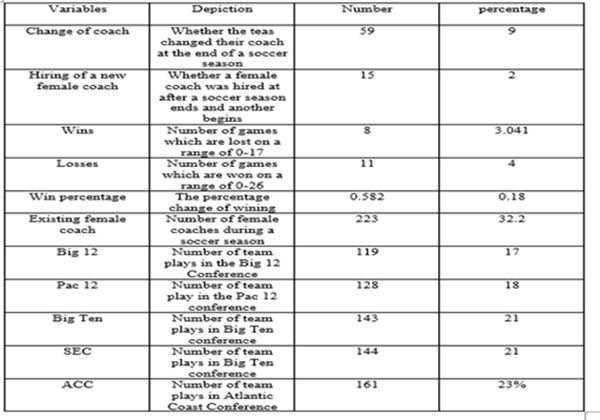

Measures and Variables

The variables of interest in this study include; change of coach to measure if the teams changed their coaches at the end of a soccer season and a new female coach to capture if a female coach was hired after a season ends and another commences. The independent variables for the research will be the gender of the coach present and team performance. Team performance will be evaluated based on the number of losses, wins, and win percentages. These independent variables denote the soccer season before a coach is changed and hence have a lag of one season.

Multiple control variables will also be used, such as the strength of opposing teams will also be utilized to influence the outcome variables. The strength of the opposing teams will be evaluated using a Rating Percentage Index (RPI). The RPI is a “mathematical rating system which considers the team’s winning percentage, the opponents’ average winning percentage and the opponents’ opponents average winning percentage” (RPI for Division I Women’s Soccer, 2018).

Additionally, surveys were used as qualitative data collection techniques to complement the results from the quantitative data collection techniques. The surveys primarily focused on female coaches in NCAA women’s soccer from five constituencies. The survey entailed obtaining feedback from coaches on whether they have experienced gender stereotypes or incongruities. Additionally, the survey sought to determine how the gender dynamic had influenced the female coaches in their careers in NCAA DI and DII soccer.

Evaluation Strategy

The hypothesis for the study, alongside the two research questions, was studied using two series of regression models. Model 1 used a change of coach

as its dependent variable and a new coach as the outcome variable. The models encompassed three estimations for each performance measure since the variables used were extensively correlated. In addition, since the dependent variables were binary, logit models were approximated.

PART III: Results

Preliminary Analyses

After data collection, we observed that only 32.4% of the teams had female soccer coaches, indicating the underrepresentation of female coaches even in women’s soccer. Furthermore, results obtained showed that 8.5% of the teams changed their coaches at the end of the season, with 2.2% of them have hired a female coach.

The study also revealed that 75% of the new coaches who were hired were men in a span of 11 years. This indicated that the underrepresentation of female coaches even in NCAA women’s soccer is most likely going to continue even in later years. Regarding team performance, the number of team losses stood at 58.2% for 20 games. Additionally, 23% of soccer teams played in the Atlantic Coast Conference, 21% in the South Eastern Conference, 21% in the Big Ten Conference, 18.4% in the Pac12 Conference, and 17% in the Big 12 conference. Finally, the presence of multicollinearity was checked in the independent variables by using bivariate correlations. Correlations that only contained continuous variables were used to get Pearson’s r. Subsequently, correlations encompassing dichotomous variables were used to obtain Spearman’s rho.

Hypothesis Testing

Figure 1 illustrates the findings obtained for coaching changes at the end of a soccer season. They also quantitatively demonstrated that female coaches were mostly hired after the poor performance of a team. The probability of changing the coach also increased significantly, especially after losing. When it comes to the issue of the role of the gender of the coach, the findings reveal that the direct influence of this variable is not substantial in each of the models. Of particular interest is the relationship between the performance of a team and the gender of the coach.

The results from the study failed to validate this hypothesis which postulated that female coaches have a greater probability of being fired following a team’s poor performance. The findings, however, substantiated the claim that there is a higher probability of hiring a female coach after a consistently poor performance. Results from the survey also indicated that female coaches are still underrepresented despite being in the women’s soccer league. The NCAA DI and DII women’s soccer has a greater representation of men than women. Female coaches also attested to having been judged on numerous occasions based on their gender.

PART IV: Discussion

In light of gender inequalities in the NCAA DI and DII women’s soccer, this research paper aimed at evaluating the gender dynamic when it comes to representation and hiring of male and female coaches. This study was narrowed down to focus on how gender affects the dismissal or appointment of coaches and how gender stereotypes and incongruities affect female and male coaches. By employing data from 11 seasons of women’s soccer, our findings illustrate that female coach have an equal dismissal rate with their male counterparts. However, female coaches have a greater probability of appointment when teams are consistently losing or for teams with high losing percentages.

The results indicate the rate of coach dismissal is higher when a team experiences frequent losses and low winning percentages. This finding is validated by research studies conducted by Foreman et al. (2018) and Holmes (2011), which assert that poor team performance is one of the most significant predictors of dismissal of coaches. The study results are also consistent with pre-existing research that suggests that gender effect in sports in the 21st century is very minimal (Heilman & Caleo, 2018). A majority of the schools in the constituencies have also implemented numerous policies on reducing biased performance judgments.

The study also reveals that female coaches stand a greater chance of being appointed when a team is consistently losing or when a team has a very low winning percentage against most teams as compared to male coaches. This result supports the claim by Ryan & Haslam, 2007 that “winning is more important than not losing in women’s college soccer because the effect of the number of games lost was not significant.” The results also support the glass cliff postulation of this research paper that women are more likely to be hired when in precarious situations.

This lends credence to Mulchany & Linehan’s (2014) postulation that “the glass cliff phenomenon is driven as much, if not by more, by the fact that man is given preferential access to cushy jobs as by the fact that women are appointed to precarious ones.” This observation has drawn a lot of debate from a wide array of researchers, with some attributing this to the undeniable ability of women to handle critical situations. In contrast, others argue that it is just a tactic used by institutions to blame the losses on the women based on stereotypical prejudices against women. Moreover, putting women in such indefensible positions puts them against their male counterparts since they are not exposed to the exact predictions as the male coaches.

PART V: Limitations of the study

One of the significant limitations in the study was the use of data from only the top athletic conferences in the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Additionally, the study focused on obtaining quantitative data regarding gender stereotypes and biases and establishing whether these aspects were statistically present and significant or not. However, the study did not specify why these stereotypes and incongruences were present.

PART VI: Recommendations for Future Research

It would be essential to include a more diverse population base for future research. This can be made possible by including more NCAA DI and DII constituencies into the analysis despite their performances. Additionally, it would be fruitful to diversify the study to include more sports such as handball, volleyball, and hockey. This will introduce a new perspective as to whether the gender biases on female coaches are widespread across all sports or whether they are only limited to female coaches. Moreover, it would be fundamental to discover the reasons behind the gender biases and incongruences. Additionally, future studies should not only be limited to female soccer coaches but should also extend to other underrepresented groups like coaches from ethnic or racial minorities.

PART VII: Practice Implications

These results of this study have tremendous implications for women’s soccer and the entire sports management practice. According to Ellemers et al. (2012), promoting women at their workplaces may sometimes cause more emotional harm than good for them. This sentiment is very close to this study’s findings, especially concerning the glass cliff phenomenon. Also, more efforts should be invested in reducing gender prejudices when hiring coaches. The hiring process should strictly be based on the grounds of merit and not on other biased and prejudiced notions.

PART VIII: Conclusion

In conclusion, the gender dynamic is fundamental for NCAA DI and DII women’s soccer. Even though soccer is classified under women’s soccer, female coaches are still significantly underrepresented. Additionally, female coaches stand a greater possibility of being hired than male coaches in the event of frequent team losses based on gender stereotypes and incongruences.

References

Acosta v., & Carpenter J., (2014) “Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal study- a 37-year update-1977-2014.”

Burton L., (2015) “Underrepresentation of women in sports leadership: A review of research.” Sport Management Review pp.155-165

Eagly H., & Karau J., (2002) “Role incongruity theory of prejudice towards female leaders” Psychological Review, 109(3), 573-598

Ellemers N., Rink F., Derks B., & Ryan K., (2012) “Women in high places: When and why promoting women into top positions can harm them individually or as a group (and how to prevent this)” Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 163-187

Foreman J., Soebbing P., & Seirfried S., (2018) “The impact of deviance on head coach dismissals and implications of a personal conduct policy ” Sport Management Review; Advance online publication

Gomez-Gonzalez C., Dietl H., & Nesseler C., (2018) “Does performance justify the underrepresentation of women coaches? Evidence from professional women’s soccer” Sport Management Review.

Haines L., Deaux K., & Lofaro N., (2016) “The times are changing….or are they not/ A comparison of components of gender stereotypes” Psychology of Women Quarterly.

Heilman E., & Caleo S., (2018) “Combatting gender discrimination: A lack of fit framework.” Group processes & Intergroup Relations. 21(5), 725-744

Holmes P., (2011) “Win or Go Home. Why college football coaches get fired” Journal of Sports Economics

Kahn M., “2007” “Cartel behavior and amateurism in college sports” Journal of Economic perspectives

Mulcahy M., & Linehan C., (2014) “Female and precarious board positions: Further evidence of the glass cliff.” British Journal of Mnanagement25(3), 425-438

NCAA, (2018) “Women’s soccer championships history.”

RPI FOR Division I women’s soccer(2018) “RPI; Formula.”

Ryan K., Haslam A., Morgenroth T., Rink E., Stoker J., & Peters K., (2016) “Getting on top of the glass cliff: Reviewing a decade of evidence, explanations and impact” The leadership Quarterly.